When you think of stories, you might think of books first. But many stories—including gender-diverse stories—are told through art, as well.

The Los Angeles Central Library, also known as the Goodhue Building after its architect Bertram Goodhue, is decorated with a sculptural program meant to celebrate the passage of knowledge over the generations. Its original sculptures, designed by Lee Lawrie, include several monuments honoring great thinkers and writers of the past. The people to be discussed in this post, people whose likenesses and inscriptions have been carved into the stones of the library, lived in societies that reinforced a gender binary. Yet through their legacies, they offer onlookers multiple reminders that gender diversity and gender nonconformity have been present in our history and mythology going back to antiquity.

Of course, it would be irresponsible to try to draw exact parallels between the trans and non-binary identities of today with gender-diverse expressions and mythological characters from thousands of years ago. Even a few decades can see a dramatic shift in the context and the language surrounding gender. Still, it would also be irresponsible to disregard the gender-diverse expressions of the past.

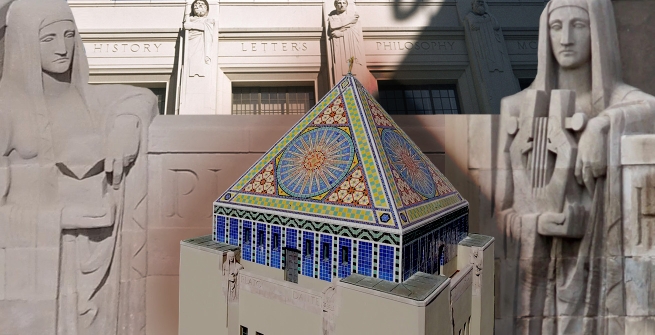

Let's take things from the top. The truncated tower capped with a pyramidion is one of the easiest to recognize features of Central Library. On each of the four sides of this concrete structure are two limestone figures known as the "Seers of Light." They are representations of people whom philosopher Hartley Burr Alexander (who came up with the theme "The Light of Learning" for the library's decorations) saw as representing the highest achievements in areas such as poetry, literature, and culture. The tower's east side holds a statue of the Greek philosopher Plato, author of the Republic and the Symposium. The Symposium, which explores the subject of love through a series of speeches given by Greece's great minds, contains a myth that has endured to the present day: the Myth of the Androgyne. According to this myth, humans were originally spherical beings with two faces and two sets of limbs. There were three types of person: male/male, female/male, and female/female. When humans tried to usurp the gods, they were punished by being split in half. Since then, Plato writes, humans have yearned for their other halves. Anyone who was originally part of a female/male pair is straight, while anyone from a male/male or female/female pair is gay.

Is this myth a reductionist depiction of queerness? Of course. As we wrote before, though, we can't draw exact parallels between queerness today and queerness in ancient Greece. It's also worth remembering that Plato was one man with one perspective, which means he absolutely had blind spots when it came to queer (and straight!) experiences.

What makes the Myth of the Androgyne significant from a gender-diverse perspective is the premise that love is the experience of seeking out a missing part of ourselves. Are men and women two mutually exclusive categories, Plato asks, or are they more akin to yin and yang, with each containing some of the other?

By the way, if the Myth of the Androgyne sounds familiar to you, it may not be because of that Greek philosophy class you took in college. In the 2001 musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch, John Cameron Mitchell stars as Hedwig, a trans rock singer who retells the myth in her song "The Origin of Love."

On the south side of the tower sits the epicist, Homer. Homer (who, if he is one person, it's debatable) probably lived around 800 BCE and is credited with giving us the earliest known work in Greek literature, the Iliad. A poem that covers a segment of the Trojan War, the Iliad brings up "the manlike Amazons" who were known to the ancient Greeks as an all-female warrior society. Amazonian societies appear in Chinese and Indian literature as well, but in Greek literature, they were depicted as antagonists for the Greeks to vanquish; a popular subject in ancient Greek art was the Amazonomachy, an Amazon battle.

As with many myths, stories change over time. Some writers from antiquity attributed a distinguishing feature to the Amazons based on a faux-Greek etymology, a + mazos, which implies "breastless" (think of the prefix masto-). It was said that the Amazons had their right breasts cauterized to make it easier to use bows and javelins. That being said, ancient art depicts the Amazons with torsos intact.

Coming down from the tower, we see six portraits of accomplished men in the fields of history, letters, philosophy, statecraft, art, and science on the Library's Hope Street façade. Representing the personification of letters is the Latin poet Virgil, who lived in the first century BCE. His most famous work, the Aeneid, takes place after the fall of Troy and tells the story of the founding of Rome. Virgil invokes the Amazons in his epic by comparing Aeneas' lover Dido, the founding queen of Carthage, to the Amazon leader Penthesilea, "a warrior queen who dares to battle men." He also evokes the spirit of the Amazons in the character of Camilla, leader of a race of female warriors known as Volscians. He calls her "a warrior dame; unbred to spinning, in the loom unskill'd. " The myth of the Amazons is generally related as a cautionary tale about women who reject the feminine role. Like Penthesilea, Dido and Camilla come to a punishing end.

On Virgil's right is Herodotus, known as the "Father of History." Herodotus, who lived in Greece in the fifth century BCE, also wrote about the Amazons in the Histories, his most famous work, citing their skillfulness in hunting and horseback-riding, their masculine way of dressing, and their lack of experience in domestic work. By his account, some of the Amazons were slain while others were tamed, to a degree, by Scythian men, furthering the myth of the Amazons as women who need correcting. (For the record, Herodotus told some whoppers here and there, but there is, in fact, archaeological evidence of female warrior graves in Scythian land, which stretched from the Danube to parts of Russia.) Despite the misogynistic tones of ancient Greek lore, however, it is safe to say that the Amazons' reputation for fierceness and independence has surpassed the male insecurities underlying their mythic origins.

Another group of people Herodotus wrote about in the Histories were known as the Enareës. They lived among the Scythians and were similar to Native American Two-Spirit people in that they served as ceremonial priestesses but were considered male at birth. According to Histories, the Enareës were made into women as divine punishment for plundering the temple of Aphrodite Urania. Elsewhere in the Histories, Herodotus describes them as "man-women" who say they were given the gift of divination from Aphrodite. These gender-diverse holy people were accepted in their society.

We can find reminders of gender-diverse history not only through Central Library's sculptures but also through its inscriptions. On the Flower Street façade, above the sculptures of Phosphor and Hesper, who represent Eastern and Western wisdom, respectively, is a quote from Lucretius' Latin poem from the first century BCE, De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things): "ET QUASI CURSORES VITA LAMPADA TRADUNT." This quote was translated by Hartley Burr Alexander as "Like runners passing on the lamp of life." In De rerum natura, Lucretius describes nature as being composed of a material that is engaged in a cycle of creation and destruction. Life goes away and reemerges as something similar to what it replaced. "Nature she changeth all, compelleth all to transformation" comes from Book Five, arguably the most popular part of the poem, in which Lucretius describes the origins of the world and mankind.

In Book Five, Lucretius brings up the portenta, a primordial race of people who were between male and female. Unfortunately, in the poem, the portenta, an apparently intersex race, die out due to malnourishment and an inability to make progeny. In ancient Rome, it was common to drown intersex infants, and in ancient Greece, they were often left to die. While Lucretius looks down on the portenta, his poem indicates that they came from the same elements of nature that produced all life. As the philosopher George Santayana stated in reference to the poem, "It is that all we observe about us, and ourselves also, may be so many passing forms of a permanent substance." This quote reminds us that our similarities outweigh our differences.

Lee Lawrie: Another view of the sphinxes flanking the Statue of Civilization at the top of the Fifth Street stairwell. LAPL Collection

Lee Lawrie: Another view of the sphinxes flanking the Statue of Civilization at the top of the Fifth Street stairwell. LAPL CollectionWhile the vast majority of Central Library's decorative sculptures are situated on the library's exterior, a trio of interior sculptures offers us more stories in the history of gender diversity. In the library vestibule at the top of the Fifth Street entrance stairwell sit two sphinxes made of Belgian marble and bronze. They appear to be "seductively androgynous," as Kenneth Breisch puts it in his book The Los Angeles Central Library: Building an Architectural Icon, 1872-1933. Resting on the sphinxes' forearms are books containing quotes by Plutarch, a Greek biographer and essayist who lived in the first and second centuries CE. The quote on the left sphinx's book says, "I am all that was, and is, and is to be, and no man hath lifted my veil." The quote on the right sphinx's book says, "Therefore, the desire of Truth, especially of that which concerns the gods, is itself a yearning after Divinity." These quotes are from the Moralia, a work which Plutarch started as a series of ethical essays but eventually came to include other writings unrelated to ethics. In the Moralia, he brings up the Festival of Impudence, a celebration in Argos in which men and women cross-dressed. Plutarch attributed the cross-dressing to the Argives honoring the courageous women who, for want of manpower, defended Argos from Spartan invaders.

The sphinxes were completed in 1930, four years after the opening of the Goodhue Building. It is worth noting that around this time, the bearded Sphinx of Hatshepsut was being prepared for its debut at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. The pharaoh Hatshepsut, who lived in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries BCE, was assigned female at birth but is depicted as a king in most of the statues of their time. (The sphinx was smashed to pieces when Thutmose III succeeded Hatshepsut in one of ancient history's most famous cases of monument erasure, so what you see at The Met is the statue pieced together with plaster to fill in the gaps.) Although a strong argument can be made that Hatshepsut's transition may have been more motivated by politics than an internal sense of their gender, the artwork that depicts them coded as male is indicative of a certain level of tolerance the ancient Egyptians had for gender fluidity.

The sphinxes appear to be guarding a statue entitled Civilization, which depicts the goddess Athena. Like the sphinxes, this sculpture is mixed-media, being made out of Italian marble, bronze, and copper. It was most likely inspired by Athena Parthenos, a colossal gold, silver, and ivory statue that once stood in the Parthenon, but which we now only know about through historical description and replicas. Born fully formed from the forehead of Zeus—depicted in the crowns of the sphinxes next to Civilization—Athena is known today as the goddess of wisdom and war. However, in antiquity, she truly was the goddess of civilization, overseeing crafts like spinning and weaving, and serving as the patron deity of the city of Athens. (Athena is also the patron of American libraries.)

Athena subverts modern gender norms in a few different ways. There's her birth, which makes Zeus both her father and her mother. (According to the earliest known account, Zeus ate Athena's mother, who was already pregnant with her!) There's the fact that a woman is associated with a "masculine" endeavor like warfare. Instead of a book, the Athena Parthenos was depicted with a shield that featured images of an Amazonomachy. Athena sided with the Greeks, however, and can be considered a foe of the Amazons. At a major turning point in the Iliad, she disguises herself as Hector's brother Deiphobus to help sway the outcome of the Trojan War in the Greeks' favor. Finally, there's Athena's association with civilization as a whole—an association that would gradually come to be seen as the purview of men alone.

These stories have all been tangential in relation to the subjects of the Goodhue Building's sculptural program. Hartley Burr Alexander's vision was focused on knowledge, achievement, and the progress of civilization. But we hope these stories remind you that gender diversity is part of human history, which makes it part of the story of civilization.

Thank you to Julia G. and Erin P. for helping with this post's research, writing, and editing.

For books on gender-diverse history and Central Library's history, art, and architecture, check out these titles!

The Los Angeles Central Library: Building an Architectural Icon, 1872-1933 by Kenneth A. Breisch

Feels like Home: Reflections on Central Library: Photographs from the Collection of Los Angeles Public Library

Spine: An Account of the Jud Fine Plan at the Maguire Gardens Central Library, Los Angeles by Jud Fine

Los Angeles Central Library: A History of Its Art and Architecture by Stephen Gee

The Library Book by Susan Orlean

The Transgender Encyclopedia by Brent Pickett

Gender Pioneers: A Celebration of Transgender, Non-Binary and Intersex Icons by Philippa Punchard

The Light of Learning: An Illustrated History of the Los Angeles Public Library by Bernadette Dominique Soter